The story in his name: G Baebius Myrismus

My friend John Ricard, who teaches Latin in person at a high school and also online through his LatinFluency.com, told me this about how Roman names worked:

G. BAEBIUS MYRISMUS. There is a man's name here: G is an abbreviation for Gaius; then there is Baebius and Myrismus. This would be a Roman citizen's name because there are three parts and that would be the praenomen, nomen, and cognomen we typically see in Roman citizen names (e.g. Gaius Iulius Caesar). The nomen is the family name (like a last name), the praenomen is what his buddies would have called him (this is where the name Guy comes from), the nomen is the family name (like a last name), and the cognomen is usually reserved to describe which branch of the family/clan he came from which could also be like a familial nickname (Caesar denotes someone who is curly-haired).

Once John helped me understand the naming system, I was able to focus my search and discovered the following: Gaius’s cognomen, Myrismus, was a Greek name often given to slaves, indicating that our Gaius might have been of Greek origin. However, there is a catch here: the ability to read and write, and therefore to serve as a scribe, was seen as a particularly Greek quality, so even a non-Greek slave could have been given that name to indicate that he had that skill set. So really all Myrismus tells us for sure is that Gaius was educated.

The nomen tells us a lot more. Baebius was the name of a wealthy extended family from Saguntum, present day Sagunto, another Roman community near Valencia. The Roman Theater of Sagunto is still used as a theater today;

Members of the Baebius family were senators, large landowners, and members of the elite. A few of them had important administrative and political posts in the first and second century.

So, it’s possible that Gaius was born a slave in this family, educated and trained to serve a member of the family with administrative responsibilities.

The story in her name: Fabia Saturnina

It’s possible that Gaius was still a slave when he met and fell in love with Fabia Saturnina. There is still very little research on women form Roman times, even their names. But if you’ve read this far you can already tell that since she only has two names, she wasn’t a Roman citizen. Saturnina was a name often given to female slaves; it referred to Saturday, the day dedicated to the god Saturn. Her first name, Fabia, was probably a feminization of her owner’s name; Fabio means “bean-farmer.”

So, now we have some evidence to guess at their love story. Maybe Fabia belonged to a Fabio who was a farmer, maybe she worked on the lands owned by the Baebius family in Sagunto. Or maybe she worked in the kitchen.

Maybe she and Gaius met and fell in love. Maybe they were parted when Gaius’s talents as a scribe were recognized and he was sent to Sagunto to work for his master. Maybe he worked hard. First he bought Saturnina; some slaves did own slaves, called vicarius/a, of their own, and these were often their spouses. Maybe they did everything to avoid having children, as those children would have been slaves and not theirs.

But they dreamed of reaching that level of citizenship, of personhood. They dreamed of freedom, dignity, family, maybe even wealth, as that’s what it would take to make their other dreams possible. They worked together to make a life for themselves. Maybe Gaius was freed when his master died, maybe he earned his freedom and freed his wife.

From Sagunto to Tarraco

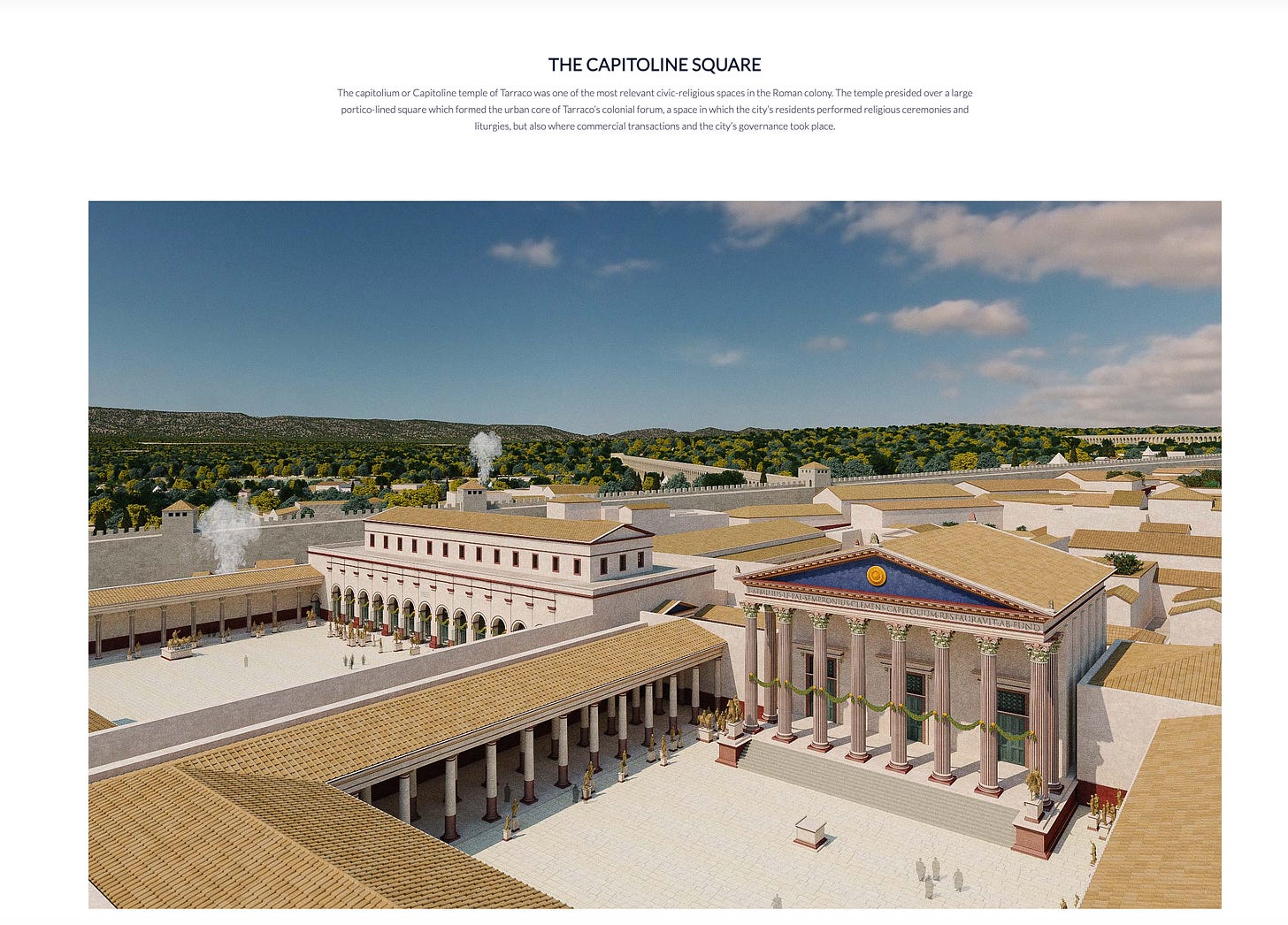

At that point the couple wanted to start their life fresh, go someplace where Gaius could earn his living as a scribe, magistrate, jurist, and where there wouldn’t be many who knew them as slaves (though there was no hiding that they were now libertos, or freed slaves). In Tarraco they had connections, as there were at least nine members of the Baebius family there at the time, one of them a woman married to a Sevir Augustal.

Now the couple could live the good life. They could start a family. They could build wealth and improve their social standing. Never again would they be invisible even when they were in the same room as their owners.

And they actually achieved their goals. For Gaius to become a Sevir Augustal was as high a social status as a freedman could aspire to. After a long struggle, years of hard work, and a lot of patience, they could determine every aspect of their own lives. They could hold their head up in society. They could leave their mark on their new city. They could feed the poor, pay for games, build monuments.

And then something happened and Saturnina died. Did she die giving birth to the long-awaited child? Was she felled by a sudden illness? We don’t know.

They’d worked so hard for so long, achieved the near-impossible, but then were deprived of the time to enjoy it together. The inscription, Uxori Optima, literally means “lovely wife.” It was a standard phrase on honorary monuments (so was “best wife and mother,” but this inscription doesn’t say that). The phrase is standard, but it speaks of Gaius’s grief.

There was one way to see his wife every day. Honorary monuments were usually dedicated to the memory of rich, aristocratic donors, like Plancia Magna of Perge above.

Gaius had an honorary monument made to Saturnina, his wife who was once a slave. He made a statue on a pedestal and put her name on it in huge letters for everyone to see, then had it placed near where he worked: in the Forum, the mall/town center/civic center of the city, so he could see his beloved every morning when his work day began and every evening when it ended.

Several centures later, Roman Tarraco was almost entirely abandoned, it’s magnificent structures crumbling, a kind of no-man’s land caught between wars in the north and wars in the south. When peace finally came and people moved back into the city, they were no longer Romans. The stones of the crumbling monuments were recycled into new dwellings. The statue was taken away. Maybe she stands in some museum somewhere, who knows? Then the pedestal was used by some enterprising late medieval homeowner who was building a house. The inscription pleased them enough that they placed it so it could be read by passers-by on the street. We can still see it there and for a moment travel back in time, put ourselves in the shoes of this long-dead couple, and experience their courage, determination, and love.